Webinars

Sponsored by

Space – The First Frontier: What affects the space required for emergency generators and how to use it effectively

This webinar navigates shows how innovations such as racking and belly tanks help make the most of the space and budget available.

Sponsored by

Building Regulations and Building Safety Bill update and the role of heat pumps

Webinar looking at the latest updates to Part L and how this will impact the design of future developments

Sponsored by

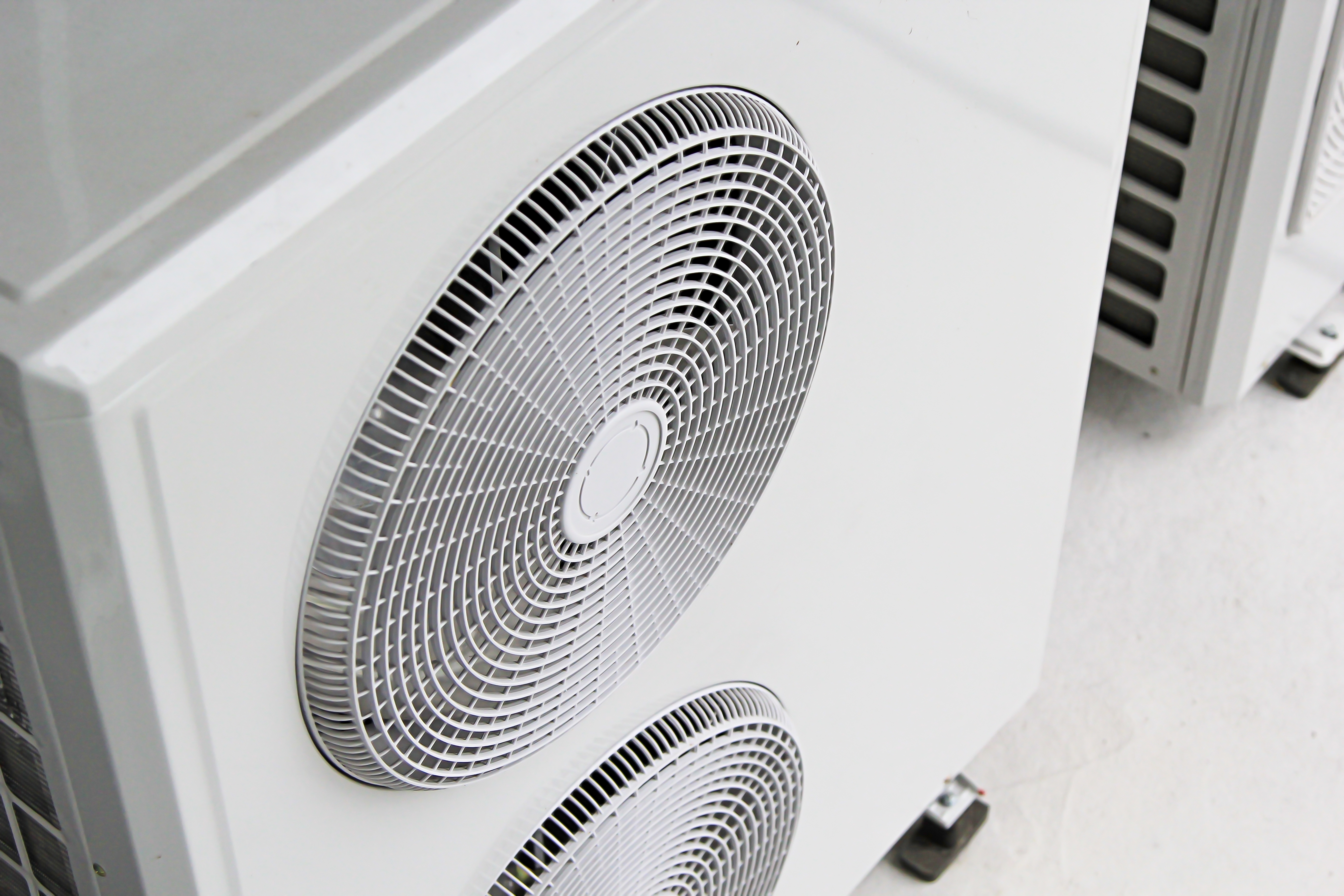

Water Source Heat Pumps and Ultra Low Heat Networks for the Multi-Residential Sector

Join Mitsubishi Electric in this webinar which explores the future of ultra-low heat network technology within multi-residential apartments

Sponsored by

Ready or not? UPS Systems Monitoring and Management

This webinar looks at today’s monitoring and communication options.

Sponsored by

Building up to a digital evolution

This webinar will show how embracing new technologies can positively impact optimisation whilst decreasing lifecycle costs.

Sponsored by

A sound solution: The impact of wastewater noise on building design

This webinar looks at the importance of adopting a full system approach to washroom design

Sponsored by

Understanding DPCVs and PICVs for Effective Flow Control in Variable Volume Systems

Webinar also explores the operation, application and common installation queries in relation to these products

Sponsored by

Smart Lighting Guide

Webinar looks at the real benefits of wireless connected lighting systems to consultants, contractors, engineers and end users.

Sponsored by

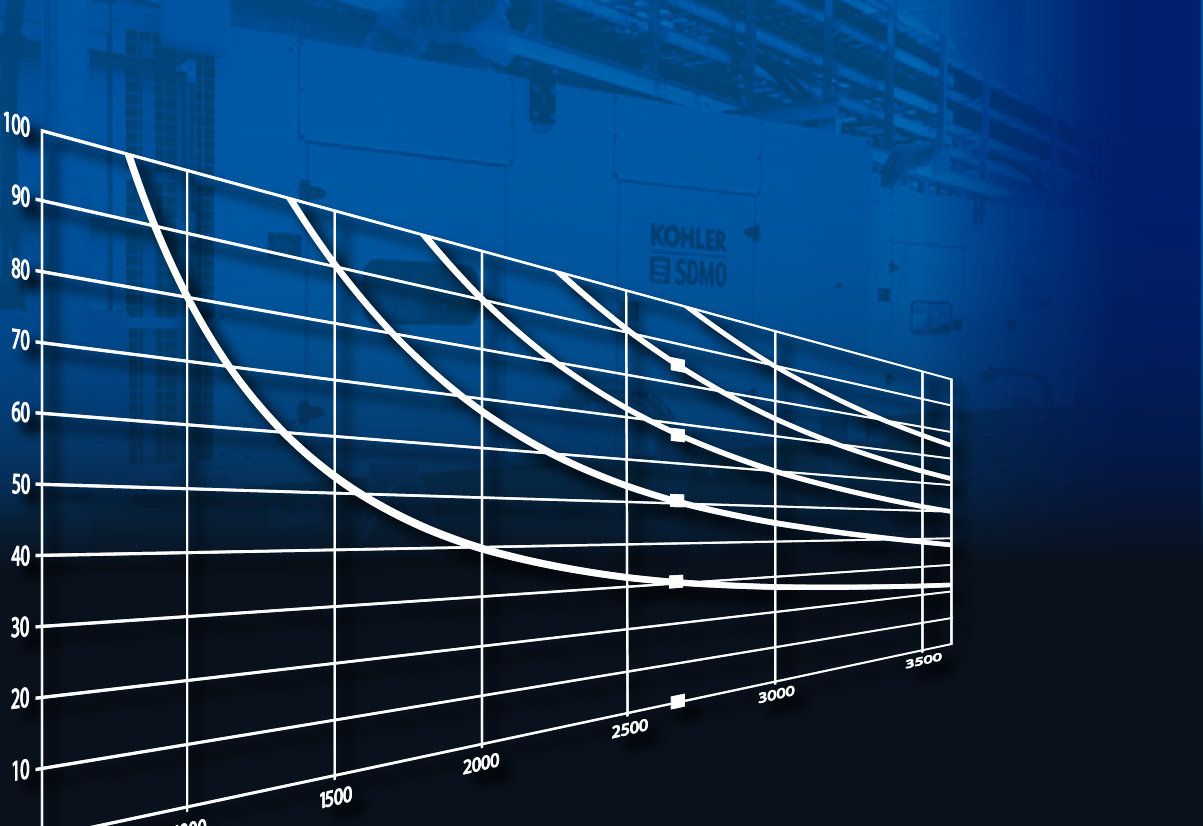

Gensets – Are you sizing comfortably?

Recent regulatory and technological changes along with their impact on sizing and selecting standby generator sets

Sponsored by

Staying in control of design to value pumping solutions

A look at various aspects of pump design surrounding pressure boosting, liquid cooling and heating, to examine how the latest intelligent design to value…